How to Unleash Your Canine Companion's Inner Dog

Who let the dogs out?

Who let the dogs out?

We love our dogs so much that we think of them as furry people, with needs that are approximately the same as ours. And while four-legged family members do need many of the same things as we do—love, emotional security, the opportunity to have fun and be playful—they also have some dog-specific needs that can go unmet, if we aren’t careful.

What dogs need, above all else, are opportunities to behave like dogs. This may sound strange, but the reality is that modern dog-keeping practices place various constraints on natural dog behavior. We’ve “de-dogged” our dogs.

Dogs are members of the family Canidae, and close relatives of wolves, coyotes, foxes, and jackals. They’ve evolved a suite of behaviors to successfully navigate their environment and to increase their chances of survival: procuring food, protecting themselves from threats, monitoring a home range or territory, mating, bearing and raising young, forming attachments.

Ethologists (scientists who research animal behavior) would say dogs are “motivated” to perform these actions; they have neural systems that are wired to offer reward, in the form of positive feelings, for engaging in these behaviors. The motivation—the behavioral need—to engage in these behaviors is present whether a dog is living as a pampered pet or as an independent, free-roaming individual.

Think about some of the ways in which modern dog-keeping practices constrain dogs’ natural, species-specific behaviors. Dogs are confined by walls or fences so they cannot roam in search of mates. They are constrained by collars and leashes so they can’t move around freely and establish a home range. They are scolded for humping; they are scolded for foraging (which we call “stealing food” or “counter-surfing”); they are scolded for soliciting food (“begging”) or attention (“being annoying”). They are told not to bark, not to roll in dead stuff, not to dig holes, not to sniff butts.

Yet these are all dog-natural behaviors. While many of these adaptations are necessary for a dog’s safety and integration into modern life, the fact remains that dogs who aren’t having their behavioral needs met—dogs who cannot express their Inner Dog—may experience chronic feelings of frustration, boredom, and anxiety.

Fortunately, we can make some easy changes in perspective and practice that can help our furry friends connect with their animal nature.

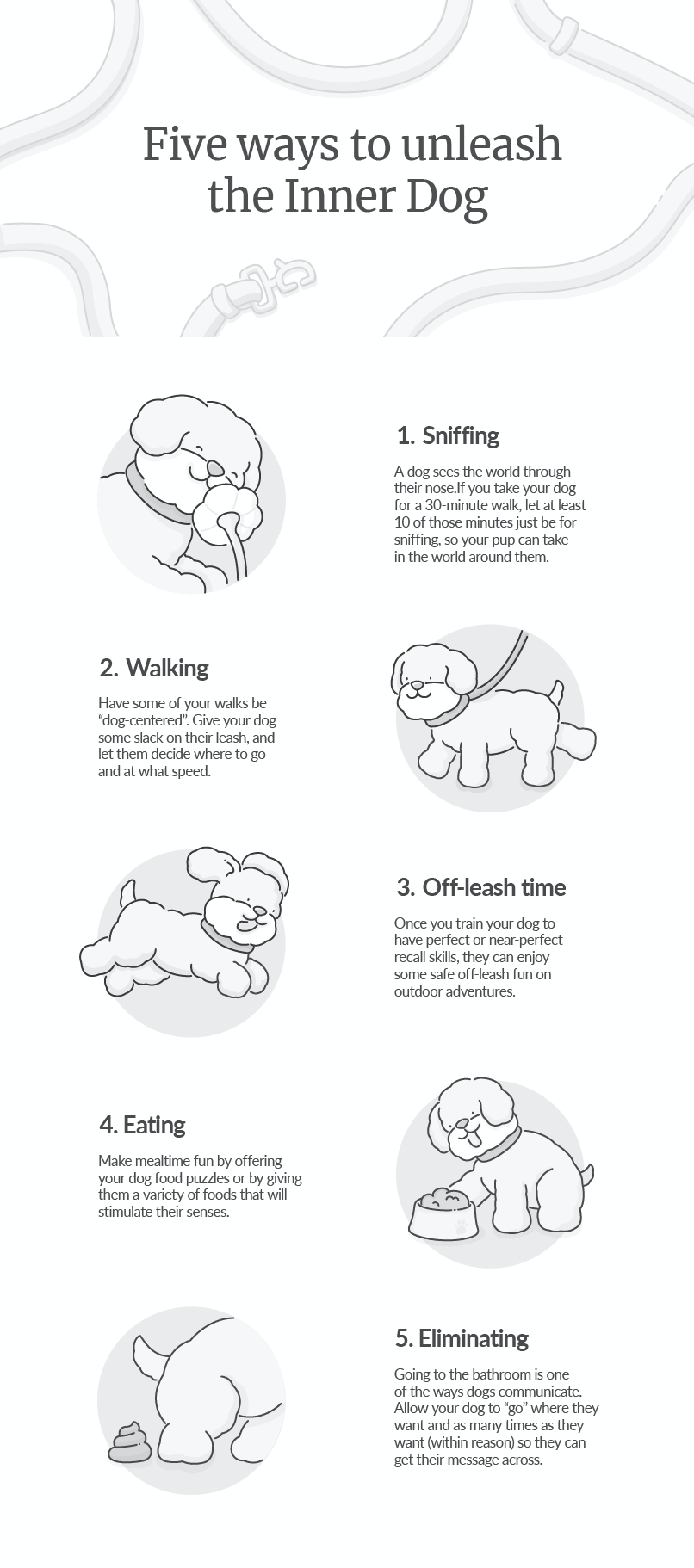

Sniffing. Humans experience the world mainly through visual stimuli. Dogs, in contrast, are olfactory creatures: They experience the world through smell. One of the easiest but most important ways to enrich a dog’s life is to make sure they have time and opportunity for sniffing.

One observational study found that, when given the choice, dogs out on a walk will spend about a third of their time sniffing. So, if you take your dog for a 30-minute walk, let at least 10 of those minutes just be for sniffing. Allow your dog time to linger over places or objects that seem particularly interesting to them. You can learn to sharpen your olfactory sense, too, or use your pet’s sniff time to take some deep breaths, enjoy the fresh air, and make some new visual observations.

Walking. “Walking the dog” is an unfortunate misnomer for the activity of taking a dog out into the world for physical exercise and sensory stimulation. Dogs don’t really want to walk. Dogs like to run, dart, stop and sniff, dart, chase, stop and sniff. When off leash, dogs rarely move in one direction but rather track back and forth and around, following scent trails, chasing squirrels, or whatnot.

If you hike with a dog in an off-leash area, you might joke that while you hiked for 5 miles, your dog must have covered at least 20. Dogs, in other words, have a lot of ground to cover. If you’re walking your dog on a leash, try to keep a loose tension, and let your dog decide where to go and at what speed (within reason, of course!). Make it a dog-centered walk. Not every walk has to be this way, but let your dog take the lead on at least some of your excursions.

The idea of a dog-centered walk goes against a common piece of training advice: “Always be the boss of your dog while leash walking. In other words, a dog should stay at your heel, and you should be in total control.”This is misguided.

Yes, a dog should be taught the skill of leash walking and should be able to walk nicely on lead when the situation calls for it. But instead of viewing leashes as a tool for dominating our dog, we might view the leash as a necessary but unfortunate safety feature of modern dog-keeping, and work with our dog to balance the necessity of leashes with the provision of ample freedom for dogs to make choices and follow their own sensory agenda.

Off-leash time. If given the choice, dogs would probably throw their leashes into the garbage. The most obvious way to unleash your dog’s Inner Dog is by providing opportunities for them to be out in the world without the constraint of a leash, typically by exploring designated off-leash hiking or walking areas or dog parks. Whether you will safely be able to provide off-leash time for your dog depends on where you live, but if you are fortunate enough to have open spaces where dogs can run free, take advantage of them.

Here’s a paradox. Sometimes the more “in control” of our dog, the more freedom she can enjoy. But control doesn’t mean keeping your pup on a tight leash, it means giving them the tools to safely run free. Meticulous training is the foundation for Unleashing. Dogs are highly cooperative and are eager to work with us; when they have a clear understanding of our expectations, they can relax and enjoy themselves without worrying about being scolded for breaking rules that may seem arbitrary and incomprehensible.

The freedom afforded by dog training is especially evident when it comes to off-leash excursions. According to survey research, the main reason people don’t let dogs off-leash is that they worry that their dog won’t come back. The better a dog’s recall skills, that is, the ability to come back to you when they’re called, the more likely they are to enjoy the freedom of being unleashed. Teaching a dog to have perfect or even near-perfect recall takes a lot of work, but the pay-off in canine freedom is well worth it.

Eating. Providing food that meets our dog’s individual nutritional needs is important. But other rewarding properties of food are equally important, including its smell, appearance, texture, and ‘mouthfeel’. Conduct taste tests to find out which foods get your dog most excited. (She will be very happy to volunteer as a study participant.) Just like us, dogs enjoy variety in their diet, so give them lots of choices.

But don’t stop there. Dogs have a whole range of feeding-related behaviors. As canids, dogs are motivated to hunt, chase, stalk, scavenge, tear, and chew. Eating a bowl of kibble doesn’t satisfy any of these behavioral needs. We can feed our Inner Dog by asking them to “work” for their food—for example by having them solve a food-puzzle toy or “forage” for kibble scattered across the floor for additional mental stimulation and enrichment.

Keep in mind that dogs are scavengers: It is natural for them to be scanning with their noses for bits of garbage or clumps of goose poop or, perhaps most delectable of all, the carcass of a dead animal. This is normal dog behavior and we certainly shouldn’t scold dogs for finding their own snacks. Whether we give them the green light to indulge in a quick chew on the deer leg they find in the forest should depend on their safety. Use your good judgment about whether these found food items are dangerous and, if not, let your dog indulge occasionally.

All conscientious dog guardians face a difficult tension between providing our dogs pleasure through food and dog treats and ensuring that they maintain a healthy weight. Modern living for dogs, as for humans, can easily lead to obesity, because calorie-dense dog food is readily available and is designed to be highly palatable—so, dogs wind up eating far more than they need. Obesity is one of the leading health concerns for dogs, and seriously detracts from their quality of life. So, practice restraint—and get your dog ample exercise.

Eliminating. One of the most severe constraints we place on dogs, and one that hasn’t received much discussion, is over their bodily processes of elimination. Humans view going to the bathroom as a very private affair; we have special rooms with doors and locks dedicated to this purpose. But for dogs and other canids, pooping and peeing are highly social, highly communicative activities relating, among other things, to territory, reproduction, social relationships, and activity patterns. We can help our companions unleash their inner dogs by thinking about poop and pee from a dog’s point of view, rather than from a human perspective.

Here are just a few things dogs might be doing when they are doing their business.

•Urine contains a great deal of salient information for dogs, so when they pee, they’re leaving messages for other dogs who might come by. Like graffiti, urine leaves a mark: “Bella was here.”

•Pee might communicate information about reproductive status, emotional state, what Bella had for breakfast, or many other things beyond the ken of human understanding.

•Similarly, poop contains olfactory information for other dogs and animals, which is often accented by a dog when she scratches the ground after eliminating.

•Poop also leaves a visual mark. Even though your dog may consider her poop to be an important contribution to the world, be a good human citizen and always pick it up. (She probably won’t notice.)

The major message here is to let your dog choose where and when to eliminate, as far as this is possible, and give her enough time to complete the messages she is trying to send.

To sum up, to be happier in their skins, dogs need more opportunities to be dogs. Modern dog-keeping practices have winnowed down dogs’ ability to fulfill their own behavioral needs, and if we aren’t careful their lives can become boring and frustrating. Luckily, with just a little bit of effort, education, and imagination, we can unleash the dog within.

Please note: Lemonade articles and other editorial content are meant for educational purposes only, and should not be relied upon instead of professional legal, insurance or financial advice. The content of these educational articles does not alter the terms, conditions, exclusions, or limitations of policies issued by Lemonade, which differ according to your state of residence. While we regularly review previously published content to ensure it is accurate and up-to-date, there may be instances in which legal conditions or policy details have changed since publication. Any hypothetical examples used in Lemonade editorial content are purely expositional. Hypothetical examples do not alter or bind Lemonade to any application of your insurance policy to the particular facts and circumstances of any actual claim.